Corporal Sharpless Fights to Get His Dispatches Out

Regardless of what one may think of the policies that led to the Indian Wars, Corporal Edward Clay Sharpless’ history as Mountainair's sole Medal of Honor awardee reflects the overwhelming odds (1:25 kill ratio) typically faced by those awarded the Medal of Honor. Sharpless, born August 10, 1853, served in the 6th Cavalry Regiment (6th CAV) during the Red River War against the Cheyenne and the Kiowa. Sharpless was a courier for the 6th Cavalry.

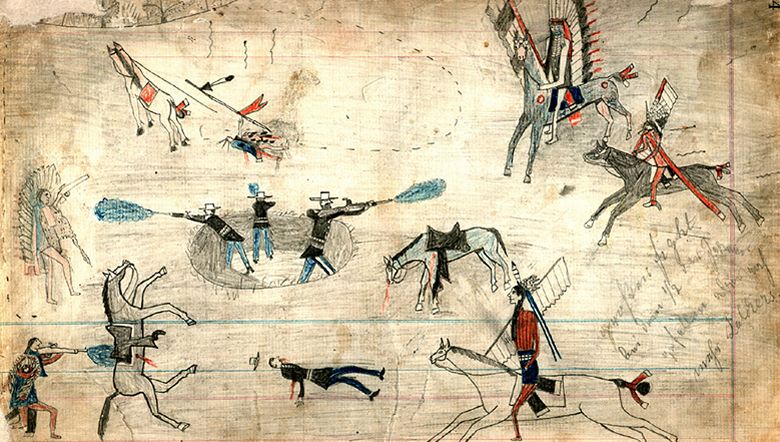

On September 9, 1874, Sharpless was riding out across the plains of Northern Texas below the wide Upper Washita River, which fed into the Red River just south of Tishomingo (in what is now the State of Oklahoma), then the capital of the Chickasaw Nation. At the time, his regiment was farther west, along the Prairie Dog Town Fork of the Red River (near Amarillo), engaging approximately 600 warriors of the Cheyenne Tribe. Sharpless was one of four cavalry scouts and two civilian guides from H Troop of the 6th Cavalry Regiment riding out across Texas that accidentally encountered roughly 125 Kiowa warriors. The Kiowa, who were armed with Spencer .50 caliber carbines and .44 caliber Model 1866 Winchester and Henry repeaters, were able to kill one of the soldiers immediately at the start of the engagement. The others fled on horseback until they came to a buffalo wallow, a natural depression just deep enough to offer the five men cover while they engaged the 125 Kiowa with their single-shot Model 1873 Springfield .45-70 carbines and .44 caliber Colt Single Action Army Revolvers.

Sharpless and the others held off the Kiowa through the day, getting off perhaps one shot to the four or five that the Kiowa were able to fire with their faster-shooting repeaters. Sharpless’ slower single-shot carbines had one major advantage over the repeaters: accuracy at distance. The Model 1873 Springfield carbine was meant to hit targets 400 yards out, a design change that reflected the tactics of those Indian tribes fighting the US Army. Tribes such as the Cheyenne and Kiowa tended to hang back beyond the range of the US Army’s predecessor to the Springfield carbine: the very same Spencer repeaters that the Kiowa were using. They would wait until a lull or mishap could be exploited, then engage in a cavalry charge. The Spencer repeater had a maximum effective range of 500 yards. The Springfield single-shot carbine was meant to hit targets at 400 yards, but had a maximum effective range of 600 yards. While the carbine was slower, in other words, it was also able to take down opponents right where the Kiowa were hanging back, waiting for their opportune moment to strike.

When the sun set on September 9, 1874, Sharpless and the others slipped away under the cover of darkness. They pared down their gear to the bare necessities, then moved out quietly. Discrepancies exist as to when the battle took place, with some saying as late as September 12, and some saying September 9, including President Grant’s citation for Sharpless’ Medal of Honor. Regardless, Sharpless and the others were able to make their way back to their unit while pursued by the Kiowa.